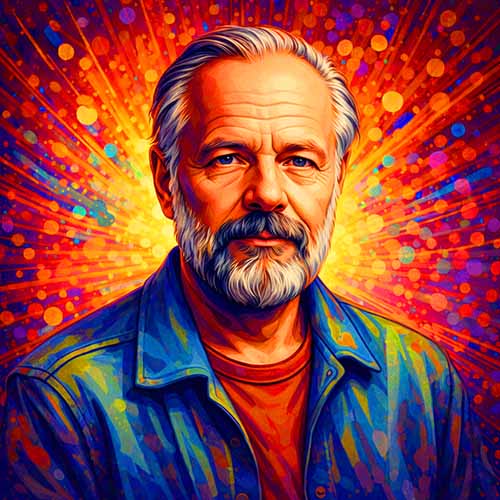

Philip K. Dick

Biography

Philip K. Dick (1928–1982) stands as one of the most unclassifiable and influential figures in twentieth-century speculative fiction. He wrote not with the tools of “hard science,” but with philosophy, paranoia, theology, gnosticism, and metaphysics — interrogating the fragility of identity, the slipperiness of perception, and the ambiguous nature of what we call “reality.” Though largely uncelebrated during his life, he has become posthumously one of the most adapted, discussed, and commercially impactful science-fiction writers of all time. His work seeded the DNA for modern cinematic science fiction, noir futurism, and the now ubiquitous question: What if the world you trust is a manufactured lie?

Born in Chicago and raised in California, Dick began publishing science-fiction stories in the early 1950s in magazines such as Planet Stories, If, and Galaxy. His early short fiction already showed his lifelong obsessions: the sentient and the inanimate trading roles, the false world hiding a truer one underneath, and the terrifying possibility that “what is real” might depend less on facts than on who is allowed to define them.

Among his earliest notable stories is “Beyond Lies the Wub” (1952), a deceptively simple narrative built around a pig-like Martian creature purchased by a starship crew. Initially treated as livestock, the Wub begins conversing with them, quoting philosophy and claiming equal dignity. Dick inverts expectations: the grotesque becomes the profound; civilization looks barbaric when measured by its own treatment of the “lesser.” In only a few pages, Dick poses a question that would return again and again: if the mind thinks — who are we to say it is not a person?

A related moral inversion animates “Human Is” (1955), where a cold and abusive husband returns from an off-world mission with his personality mysteriously altered — but improved. He is suddenly kind, gentle, and affectionate. The story asks whether humanity is defined by biology or by conduct. If someone becomes more human after an alien exchange of identity, which self is the “real” one? Dick’s answer is quietly explosive: ethics and empathy, not anatomy, are the true markers of personhood.

Alien landscapes in Dick are rarely just scenery; they are moral mirrors. In “Strange Eden” (1954), explorers land on an Edenic world inhabited by a seemingly prehistoric woman who warns them against repeating mankind’s ancient mistakes. The men — representing the typical colonial scientific impulse — assume dominion is virtue and self-control is weakness. The tragedy of the tale is not in violence but in recognition: paradise is always destroyed by the people who believe they deserve to own it.

Dick’s preoccupation with death, transcendence, and the border between material and spiritual appears in “Upon the Dull Earth” (1954), a story saturated with eerie theology. A young woman attempts to commune with angels — beings made of light — and the experiment unravels into a metaphysical catastrophe. When she dies, her lover tries to resurrect her, and reality itself begins to warp. The implication is terrible: there are realms adjacent to ours that will answer when called, but nothing on the other side is compelled to honor our intentions.

Dick often confronted systemic injustice not as allegory but as direct indictment. In “James P. Crow” (1954), society is run by robots that treat humans as an inferior class. Dick reverses the power relationship of racial segregation without disguising the analogy: forced tests, social humiliation, and pre-determined inferiority masked as “objective policy.” The story argues that no metric or machine can sanctify inequality — and that replacing human bigots with mechanical ones changes nothing essential about oppression.

Beyond the short stories came the novels that would cement his legacy. The Man in the High Castle (1962) imagines an alternate history where the Axis powers won World War II and partitioned the United States. While outwardly a political counterfactual, the book is spiritually and philosophically unstable on purpose: characters consult the I Ching, reality seems to flicker, and even history may not be what the world believes it to be. The novel won the Hugo Award and later became the basis for the acclaimed Amazon television series, bringing Dick’s core themes — authoritarian epistemology and the terror of enforced consensus — to new audiences.

Although he died young, Philip K. Dick’s imaginative afterlife exploded. His fiction has inspired an extraordinary list of films and series, including Blade Runner (from “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”), Total Recall (from “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”), Minority Report, A Scanner Darkly, Paycheck, Screamers (from “Second Variety”), The Adjustment Bureau (from “Adjustment Team”), and the anthology series Electric Dreams, as well as the prestige adaptation of The Man in the High Castle. Few authors — perhaps none — have had so many large-scale screen interpretations interrogating the same interconnected cluster of anxieties: surveillance, memory manipulation, corporate states, disposable identities, and the commodification of truth.

Dick’s voice remains singular not because he predicted gadgets, but because he anticipated the psychological climate of the information age. He foresaw the moral hazards of simulation, the soft totalitarianism of data-driven institutions, the commercialization of consciousness, and the possibility that reality could be edited without the subjects ever noticing. In his world, the greatest danger is not that we live inside a falsehood — but that we stop asking who built it.

He died in 1982 at fifty-three, just before the release of Blade Runner — the first of many adaptations that would carry his legacy into global culture. In death, he became what he never fully was in life: a central architect of modern science fiction. His work continues to be read, revisited, filmed, debated, and assigned — not as curiosity, but as an intellectual toolkit for surviving the twenty-first century. In a world increasingly mediated by screens, algorithms, and narratives of convenience, the literature of Philip K. Dick endures as a warning, a mirror, and an invitation to resist the easiest lie of all: that what we see must therefore be true.